Busting Down Brick Walls with Tax Records

Dig Into this Neglected Resource

Taxes – something everyone complains about and hates to deal with. Benjamin Franklin said it best – “Nothing is certain but death and taxes.”

This maxim applied to our ancestors too and that is a fortunate thing for us! An ancestor’s death produced probate records and these can be valuable resources but we should not overlook tax records as they sometimes hold the key to busting down that brick wall.

This blog will explain a few ways in which tax records can be used to crumble your brick wall!

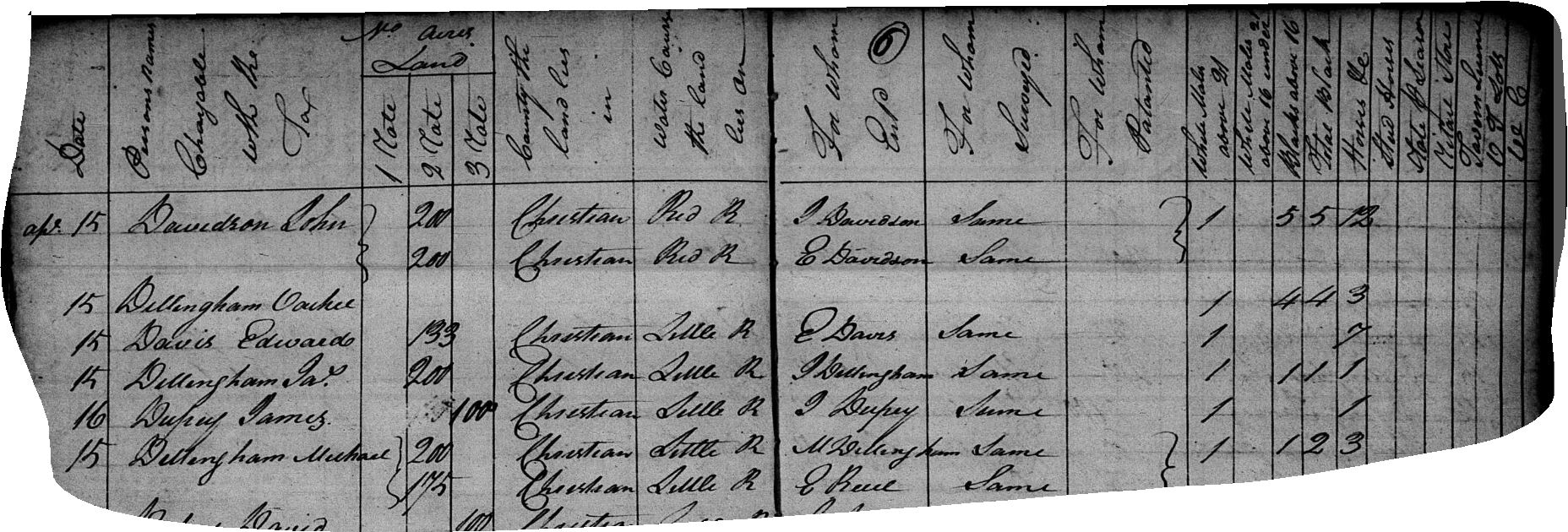

Over time, Americans have been taxed on everything from real estate to livestock. When they have survived, these records can give us an inside look into our ancestor’s lives. What did they own? Land? Slaves? Horses? Cattle? Carriages? Dogs? These are just a few of the things that have been taxed over the years.

And even if your male ancestor owned NONE of these things, he typically had to pay a poll tax, just for existing. This was also called a “head” tax. These records can be used as a substitute census to see who was living in a specific area at a given time. Adult females may not have paid a poll tax but they did pay taxes on personal property and real estate.

At various times, before the institution of the federal income tax in 1913, the federal government has levied taxes of various kinds. However, we will focus here on state/local taxes as being the most valuable for genealogists. If you have ancestry in Virginia or Kentucky, you are most fortunate in that their tax records have (mostly) been preserved since 1782 (for Virginia) and 1792 (for Kentucky). Remember Kentucky was once a part of Virginia as well. Tennessee has scattered tax records. Illinois and Missouri also have records often located in county courthouses or various archives. Be sure to also check FamilySearch.org to see what they might have on a particular locality you are interested in. For Illinois, check IRAD as well.

So how can you use a tax record to bust down a brick wall? Several ways...

Here is a problem I was working on in Livingston County, Kentucky – I was seeking to learn the parents of James A. Williams who married there in 1857. The 1850 census showed a promising candidate with a James Williams, age 20, heading a household consisting of only one other person – Mahala Williams, age 45. Was this a young man and his mother? Was it the James A. Williams who married in 1857? How could we learn more?

Beginning in 1857, I followed the tax records of Livingston County year by year backward in time. The middle initial “A” helped to keep him separate from other James Williams’ in the county but I could also tell it was him each year by what he owned – generally, taxpayers did not gain or lose much livestock each year. For example, a man with only 1 horse will not suddenly have 8 horses unless there was an inheritance. In 1851, James A. Williams was listed as paying a poll tax and was taxed on 2 horses and 1 cow. The only other James in the county that year had a middle initial of “Y.” The 1850 tax list (the year in which the census listed James A. as age 20) did not have an entry for James A. Williams. It only contained an entry for James Y. Williams who was obviously an older man listed a white male over 21 years old and having 3 children between 5 and 16 years old. However, the 1850 tax list of Livingston County does have an entry for Mahala Williams, the 45-year-old living with a James in the census that year. Mahala paid no was taxed on 3 horses and 3 cattle. She did not pay a poll tax for a male over 21. Mahala is not found in any tax roll from 1851 to 1857. So in the very year in which James A. Williams turns 21 years old, he appears on the tax rolls and is taxed on livestock and Mahala Williams is no longer taxed on any property. Conclusion: James A. Williams is the son of Mahala Williams and he began to be listed on the tax rolls in 1851, since he turned 21 that year. James A. Williams’ tombstone gives his date of birth as 9 December 1829 so that also correlates with the tax lists and census record.

Another example: I was seeking to determine the relationship of Andrew Reed to John Reed. The 1796, 1797, 1798, and 1799 tax lists of Hardin County, Kentucky indicates Andrew Reed with 1 white male over 16 and under 21 in addition to 1 white male above 21. The 1800 tax list of Hardin County shows Andrew Reed with only a white male above 21 and NO white males from 16 to 21. However, a new entry that year for John Reed indicates he paid a poll tax for 1 white male above 21. No other Reeds in the county lose a male between 16 and 21 in 1800. Conclusion: John Reed was probably the son of Andrew Reed. Of course, other records should be used to confirm or refute this hypothesis as John could be a nephew or other relation.

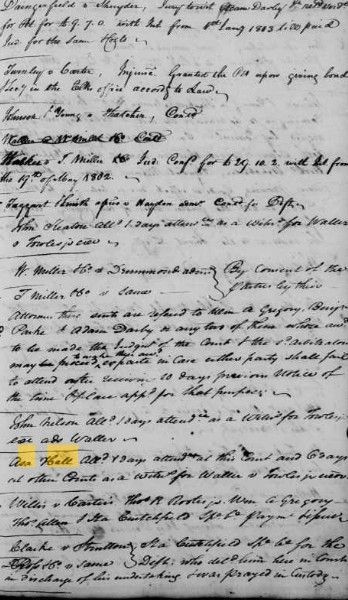

Tax records provide us with information on an ancestor’s migration to and migration from an area. When reviewing tax lists, it is my recommendation to note the date taxed whenever given. This can help you to reconstruct a neighborhood and tell who lived nearby. In addition, be sure to check the end of each tax list and often tax collectors will include additional information such as those who were delinquent in paying with notations such as “Gone to Texas” (often abbreviated GTT) or “left the county.”

If an ancestor does not appear in a particular year, be sure to check the county court order books as he may have been exempted for some reason. Also check the laws of the state you are working with to make sure you understand who and what was taxable. For example, ministers were often exempted from taxation.

This just represents a very brief overview of how tax records can aid you in your research. Seek them out as there are many other ways they can help you. For example, Virginia has both land and personal property taxes on separate rolls. Other states such as Kentucky combined them.

For more details on tax records, see Carol Cooke Darrow, CG and Susan Winchester, PH.D., CPA, The Genealogist’s Guide to Researching Tax Records, (Westminster, Maryland: Heritage Books, 2007).

Backstory Bloodhound can assist you in breaking through that brick wall using tax records and other often neglected local resources. See the Services page for more information on this.