Is Your Source a Copy of a Copy?

Check That Source and Get as Close to the Original as You Can

As genealogists, we rely on records. We have to have them. The more the better to prove our ancestry. Records give breadth and depth to the bare bones of an ancestor’s life. We try to squeeze every drop from the precious few that we have.

But what are these records? Can we trust them? Are they reliable? Are they the best available? In many situations, the records we use and rely on are not the originals. Many are transcriptions or copies. And yes, some are even copies of copies.

In today’s digital age, genealogists are often too dependent on online sources. Ancestry, FamilySearch, Findmypast, and other subscriptions are great. Many contain “original” records and some are even indexed. But do you as a researcher take the time to actually go to the original record? The indexes we have are wonderful but imperfect – humans are doing the indexing. No matter what that online tree says or what the index says, find the original record. For example, the website of the Illinois Secretary of State - www.cyberdriveillinois.com - contains death records of Illinoisans from the beginning of the recording of vital statistics in 1877. However, this is merely an index of the death register books typically found in the local county clerk’s office. And, what’s more, the register books are also not the originals. A physician or local official actually completed a death certificate – that is the original record. When they have survived the whims of local officials, these death certificates are typically in vaults at the local courthouses. So here is a case of the online version being a copy of a copy or at twice removed from the original. It has been my experience that the original death certificate typically contains much more information. Often the person copying the information into the register omitted much vital information. For example, the death register book might indicate a birthplace of Tennessee for the deceased, yet, if one takes the time to find the original death certificate, it will say born in Rhea County, Tennessee. Now which would you rather have? A county will certainly narrow down your focus.

The above principle is also true for birth and marriage records. You will find the register books in the courthouse but these are not the original records. Take the time to get the birth certificate, the marriage license, the marriage bond, and the marriage return if available. I can’t even count the number of times I have found that when pulling the original marriage record a parent signed a consent form. The consents are not usually in the marriage registers. The online indexes certainly do not bother providing that information but it is so rewarding to extend a line by another generation. Original birth certificates provide much more detail – often giving the county of parents’ births, a parent’s middle name, the birth order of a child (which helps you discover unknown children), and much other valuable information.

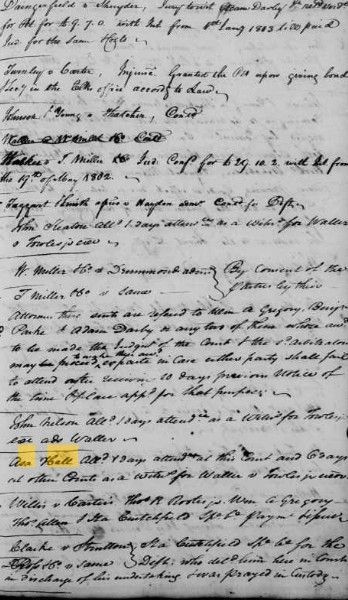

Vital records are not alone in being copies of copies. Wills are one of the most valuable and sought-after genealogical records. Of course, the will in the courthouse is a copy of the original. If there was a court case devolving from the will, another copy was typically made. Transcription errors can and did occur. This is also true for deeds. They are copies which were transcribed by a local clerk. Finding an original will or deed is indeed difficult unless they have been passed down within the family. Most, unfortunately, do not survive, so as genealogists we have to be satisfied with the copies.

Almost all records in the county courthouse are copies of the originals. Naturalization certificates are not the originals. Neither are military discharge certificates. The originals were kept by the owners.

What about Bible records? What a goldmine these can be! Yet, when looking at the source, it is important to examine it closely. Is it an original or a copy? Look at the handwriting. Is it all the same? Did the person who wrote it down have actual first-hand knowledge of the event? Entries in a Bible which has births in the 1700s and the late 1800s was likely written by different individuals or by a person later entering what he had been told or simply recopying it from another source. Remember I could go out and buy a Bible today and enter a date of birth for my grandmother in it – that doesn’t make it the correct date.

Have you ever found a listing of births and deaths within a probate record or a pension file? The nature of these vary widely. Sometimes they are originals. Sadly, individuals seeking to obtain a federal pension would send in their Bible records to prove their ages or widows would seek in this manner to prove a date of marriage. These Bible records were typically kept by the federal government and not returned to the applicant. In other cases, one can tell that an attorney or copyist merely copied the information from a family Bible to which they had access. Typically, in probate or guardianship files, the records which appear to be from a family Bible are merely copies made when the original was brought to the courthouse.

Census records are among the most widely used by genealogists. These decade-by-decade accountings of the whereabouts of our ancestors and their households are a true treasure trove. Yet in many cases, the records we rely on are third or even fourth-hand derivatives of the original records.

During the first four federal census enumerations from 1790 to 1820, assistant marshals were required to make only one set of their records. However, many made copies of their works and arranged them (unhelpfully, I might add) in alphabetical order. These copies were sent to Washington and the originals were often discarded. Thus, you get the situation such as in Smith County, Tennessee in which an ancestor whose surname begins with an “H” is listed with all other people whose surnames begin with the same letter. While we are grateful to have these records, how much better would it be to have the original where neighborhoods were preserved intact? (Note: Not all of these early census records were re-arranged in this manner.)

By 1830, federal law required two copies of the census schedules to be prepared. One was to be retained by the district court and one was to be sent to Washington. The one we now have available and microfilmed by the National Archives is generally a copy and not the original. The wherabouts of the originals is an unsolved mystery. How can you tell if you are looking at the original or merely a copy? Look at the handwriting on the document. Does it change from district to district? If not, it is likely a copy made by a clerk.

We all love that 1850 census schedule where we get every member of a household’s name for the first time. But chances are we are looking at copies here as well. After each census was taken in the years 1850, 1860, and 1870, the original was to be displayed at the county courthouse and then retained by the county. The supervising assistant federal marshal made a copy to send to the state’s or territory’s secretary of state. Then the state or territory secretary of state was to make a federal copy to send to Washington. Of course, these copies of copies are what we are now looking at on microfilm, Ancestry.com, FamilySearch, and other websites.

What effect did this copying have? I will give you one example. The 1860 Marshall County, Kentucky census copist must have been either lazy or quite neglectful. Almost every single person is identified by initials – thus, Fanny Ellen Mathis, age 18, is merely F. E. Mathis. Did you ever notice that a lot of people have rounded ages in the census? 40? 50? rather than 41 or 53. I suspect some copyists just rounded to the nearest number. Every wonder why stepchildren or others with different surnames are listed in the census with the head or household’s surname? In many cases, it is because the copyist failed to copy their surname from the original. The use of ditto marks was too easy for a tired copyist.

So what happened to the originals in these cases? County officials often used them for scrap paper or even burned them. The state copies were sometimes given out to local politicians to use for mailing lists. If you are researching in Wisconin, the Wisconsin State Historical Society does have the original state copies for that state from 1850 to 1870.

A diligent researcher can occasionally find the originals if the local county officials were careful to preserve them. For example, the original 1870 Pope County, Illinois census is still in the county clerk’s office. A comparison of this original to the National Archives microfilm copy indicates many discrepancies – differences in names, differences in ages, differences in birthplaces, etc. Omissions of a few individuals altogether was discovered. An entire section in northeast Pope County is missing from the 1860 schedule sent to the National Archives. I suspect the enumerators did not neglect to count everyone who lived in this section – my suspicion is that the copy available at the National Archives somehow did not retain that part of the enumeration.

The 1880 census was the first one in which the Census Office took over the enumeration from the U.S. marshals. In this census, each district had a supervisor who managed the copying. The originals were retained by the county. We all are aware of the almost complete record loss of the 1890 census. Beginning with the 1890 census and continuing thereafter, Congress made a decision to finance only one copy of each census. Any additional copies were to be paid for by the counties – most did not have the funds to take advantage of this option. Therefore, the National Archives copies we have for 1900, 1910, 1920, 1930, and 1940 (and any surviving 1890 schedules) are the originals.

For more detail on census records, refer to William Dollarhide, The Census Book: A Genealogist’s Guide to Federal Census, Facts, Schedules, and Indexes, (Bountiful, Utah: Heritage Quest, 2000).

One of my personal favorite records to work with are the tax lists. It is certainly not because they are so exciting but rather because they can help sort out individuals with the same name and also help prove relationships (believe it or not). They are wonderful in placing in individual in a specific place as well. Yet the tax records we are usually viewing are copies. Typically, a county official made the rounds within his jurisdiction, carefully listing names and items to be taxed. He then turned his records over to the county tax official where a copyist transcribed them into a tax book. These were usually placed in semi-alphabetical order (all surnames beginning with “B” listed together, for example), therefore again losing the layout of neighborhoods. However, sometimes the date the tax official visited the individual is listed and from these, a diligent researcher can reconstruct neighborhoods to some degree. All individuals taxed on the same date by the same official likely lived closely together.

When working with records, researchers should always search out the original record whenever possible. It takes effort but most often is rewarded with good results. It is true that we often have to be satisfied with copies, but we should always be aware that what we are examining is merely a copy and, in that case, we must understand the record’s limitations.