Writing a Proof Argument

What to Do When All Else Fails

Sometimes in our genealogical research, we reach a dead end. There is evidence indicating that a particular thing occurred or that a particular relationship existed but there is no specific document proving it. This can be very frustrating but it does not have to be the end of the story.

What can one do in this situation? One excellent option is to write a proof argument. Here are some steps I use to write a proof argument on a genealogical problem.

1) Make absolutely sure a proof argument is needed. Make sure no document you have found or could reasonably be expected to locate gives the answer you seek. Lack of access to the document is not a valid excuse here – if necessary, travel to the repository or hire a competent professional researcher to obtain the expected record. Only when specific documentary proof does NOT state what you believe to be the case should you write a proof argument.

2) Think about why you believe your conclusion is accurate. Is there anything that could lead one to another conclusion? You will need to explain that if so. You will want your reader to be convinced that your argument is the correct answer.

3) A proof argument is basically an analysis. I find it helpful to first put everything I know about the problem into a timeline. There are many ways to do this but arranging what you know in a timeline fashion can often help you see discrepancies that exist or things you may not have otherwise noted.

4) Then I write up the problem. What is my specific objective? Is it to prove lineage for a lineage society? Is it to prove parentage? Is it to separate men of the same name? The more specific you can be with your objective, the better. Tell the reader what you are proving. Be thorough, but also concise. Not everything that appears in your timeline for example, is relevant to resolving the problem or even arguing your case. Include only what is!

5) Then explain your hypothesis. What is it you believe the accumulation of evidence and the results of your analysis of prove?

6) Discuss the resources you believe are relevant. Why does a record not exist specifically proving your hypothesis? Did the courthouse burn, for example? What shortcomings do existing records have? Here you are ensuring your reader that you know the relevant record sources and have examined all that could potentially prove or even disprove your case.

7) Present the information you found, listing the strongest evidence first. Take the reader step-by-step through why you believe your hypothesis is correct. Explain why other explanations are not satisfactory. Present the information in a logical sequence. If necessary, break the proof argument into sections if there are multiple aspects of the problem. If you are disputing something already accepted as evidence by others, be very clear as to how and why. Where did that explanation err and why is your correct? As Elizabeth Shown Mills indicates, Explain, Explain, Explain. Separate fact from what is merely an opinion.

8) Cite your sources! Cite your sources? Did I mention you must cite your sources?

Evidence presented with source citations has no value. To be convincing you must cite your sources and clearly demonstrate how those sources lead one to the only logical conclusion – that which you are seeking to prove.

9) Summarize your findings again by mentioning the most significant and convincing evidence.

The Board for Certification of Genealogists defines proof arguments in this fashion:

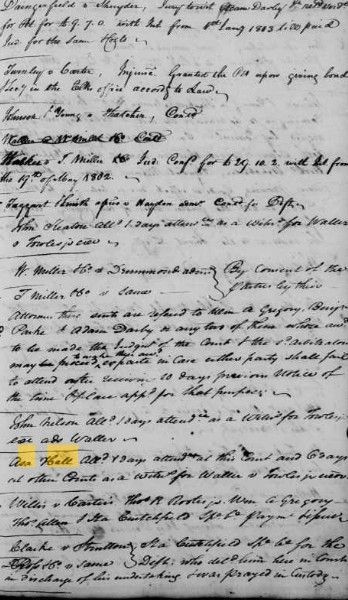

“Proof arguments are extensive documented narratives that often include figures, tables, or other enhancements. Genealogists use proof arguments to explain challenging cases, especially those where thorough research reveals significant conflicts between evidence items or an absence of direct evidence.” Board for Certification of Genealogists, Genealogy Standards, Second Edition, (Washington, DC: Ancestry.com, 2019), page 35. graph

I have attached two proof arguments I have written in the past on my website. Go to the Services Tab on this site and click on "Simple Proof Argument" or "Complex Proof Argument" to see two different types of arguments. Many people desire to join a lineage society and a proof argument is a great way to do this when no specific document provides evidence of a specific relationship. The Simple argument here was used to document my wife's line to become a Pope Pioneer (Pope County Historical Society). The Complex Argument here was to assist a distant cousin in getting our common ancestor listed correctly in the Daughters of the American Revolution (DAR) database. Prior applicants were accepted with faulty documentation - there were many John Allens in 1700s/1800s Mecklenburg County, North Carolina. This proof argument disambiguates them, establishes the correct identity for the Revolutionary War soldier John Allen, and also provides proof of the identity of his two wives.

Backstory Bloodhound would be happy to assist you with assembling the evidence and composing a proof argument.